“Flow state”—the feeling that you’re so focused that you’re lost in your work—is a battleground.

On one side, we have developers who frequently fight to protect their workflows by staving off meetings and Slack messages. On the other, managers and coworkers who have good and bad reasons for interrupting but tend, either way, to underestimate the costs of those interruptions.

Before I started writing this article, I thought the situation was simple: Developers need time and space to enter a flow state, but once they’re in a flow state, they’re at their most productive.

Surely, there are good reasons to interrupt—high-priority bugs, important calibration meetings, a fire in the building—but it otherwise seemed obvious to me that companies and development teams should work toward optimizing away from distraction and toward focus.

Why are companies hiring developers, after all, if they’re going to distract them from developing?

Over the past few weeks, though, I read over a dozen papers on flow state and developer productivity. The nuances of flow states are much more complex than I thought, and the black-and-white battleground image I had was simplistic. Almost everyone, as it turns out, is wrong about flow.

Flow state: What it (really) is and why it’s been watered down

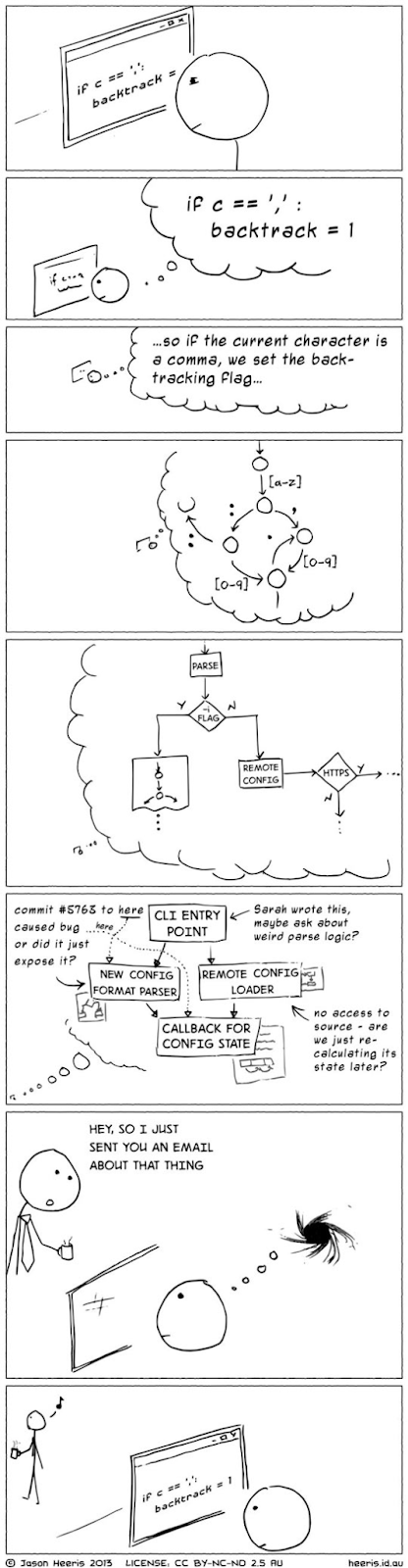

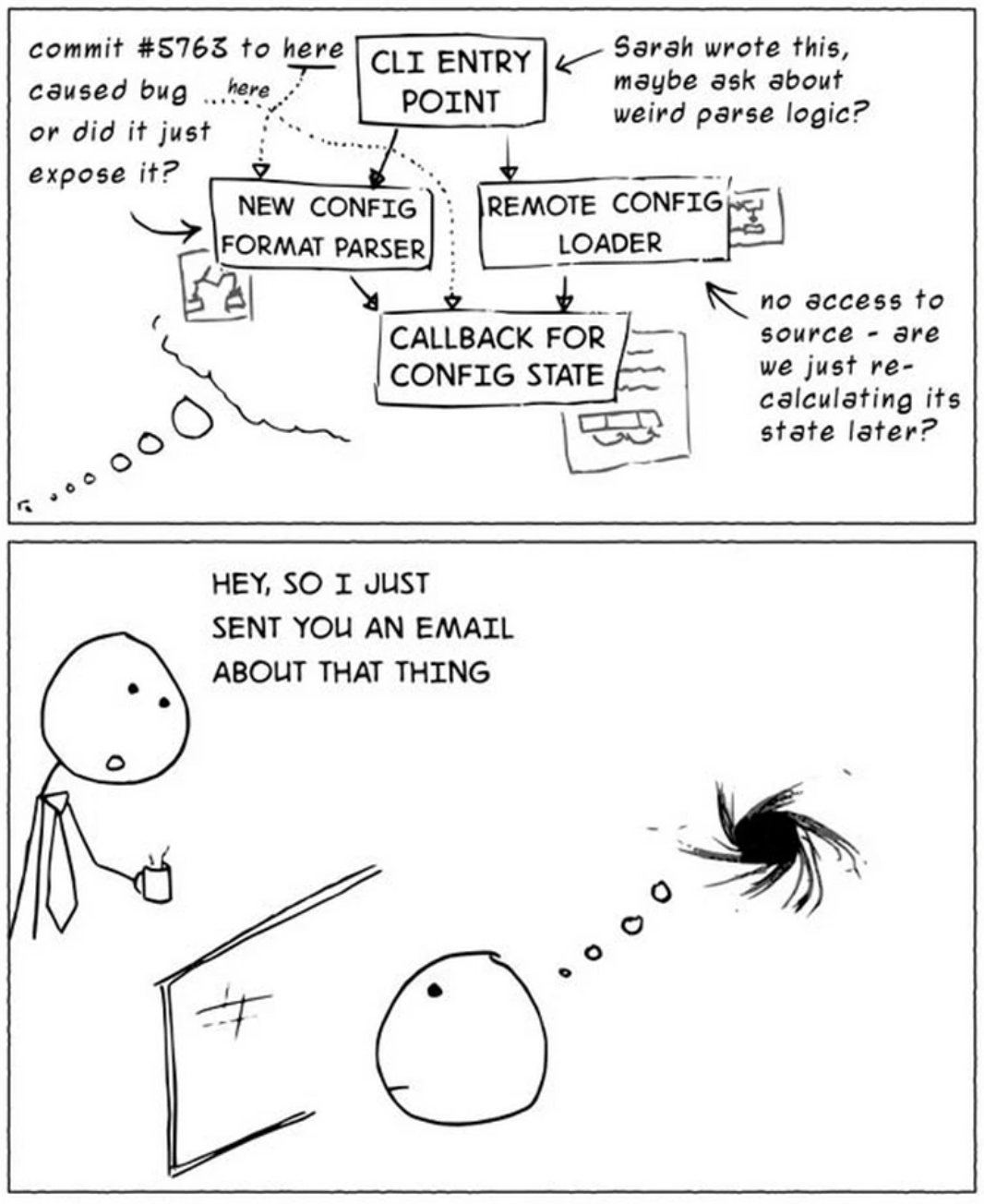

When I think of developers and flow state, I (and I’m sure many others) think about this comic by Jason Heeris.

In it, a developer is facing a problem and is gradually constructing the scaffolding to a solution. Suddenly, a coworker pops in to say, “Hey, so I just sent you an email about that thing,” and the developer’s thought bubble bursts. The coworker walks away whistling while the developer returns to the screen, and the unsolved problem remains—all the progress has evaporated.

This comic, made more than a decade ago, resonates because it really does reflect a common experience for developers. But when we capture this experience so simply, what do we miss? That’s what I set out to learn.

Flow state origins

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a Hungarian-American psychologist, is often known as the “father of flow” because of the pioneering research he did on the subject in the 1970s.

The original emphasis of this research, however, wasn’t on sheer focus nor on the cognitive load of solving complex problems. Csikszentmihalyi was most interested in figuring out when and how people were able to work without needing to think or reflect on their work while they did it.

Now, “flow state” has all sorts of associations—some scientific, some folk, and some a mix of both. For many, the term has just become a dressed-up version of focusing.

Flow state, in its original meaning, had little to do with complex problem-solving. Csikszentmihalyi’s initial inspiration was painters who would, he said, “finish a work of art, and instead of enjoying it…put it against the wall and start a new painting.”

Their drive wasn’t about the painting, he realized—it was about entering, maintaining, and enjoying what he’d eventually call a “flow state.” A flurry of studies followed in the 1980s and 1990s, bringing the concept closer and closer to public understanding.

Beyond the arts, many of the people most interested in flow were athletes. After the Dallas Cowboys won the 1993 Super Bowl, for example, the coach, Jimmy Johnson, credited Csikszentmihalyi’s book on flow, saying, “My team has won because of this book.”

And in 2000, Malcolm Gladwell wrote an article analyzing why Jana Novotna, a professional tennis player, “choked” at Wimbledon. His argument: Novotna failed to maintain a flow state.

I was surprised initially, but it makes sense.

Both arts and athletics involve a lot of deft physical movement, and I could see why professionals in those fields would benefit from learning to resist overthinking so they can “just do it.”

Almost every profession involves some need for focus, however, so you can see why, over time, the idea of a flow state breached its original limits. Now, “flow state” has all sorts of associations—some scientific, some folk, and some a mix of both. For many, the term has just become a dressed-up version of focusing.

What flow state misses

I’m typically not one to gatekeep a term. But the more I read the research and the more I talked to developers, the more I felt our watered-down definition of flow state leaves us without a lot of the richness that made the concept so popular in the first place.

Before I started writing this article, I thought the situation was simple: Developers need time and space to enter a flow state, but once they’re in a flow state, they’re at their most productive.

Flow state became popular primarily because of what it does and how it feels. But too much emphasis on the feeling of being “in flow” can mean losing sight of what you should actually be doing. We know that the most impactful development can’t be measured in lines of code, but we can still slip into overemphasizing flow and fighting against all interruptions—whether they break focus or align focus.

The greatest threat isn’t an external interruption but an internal fragmentation

In other words, flow—which is, in its ideal form—a means to productive, creative ends, can turn into an end in itself.

A high-priority vulnerability, for example, warrants an interruption. The lost focus is likely a good tradeoff. These “worthy interruptions,” however, extend beyond meetings.

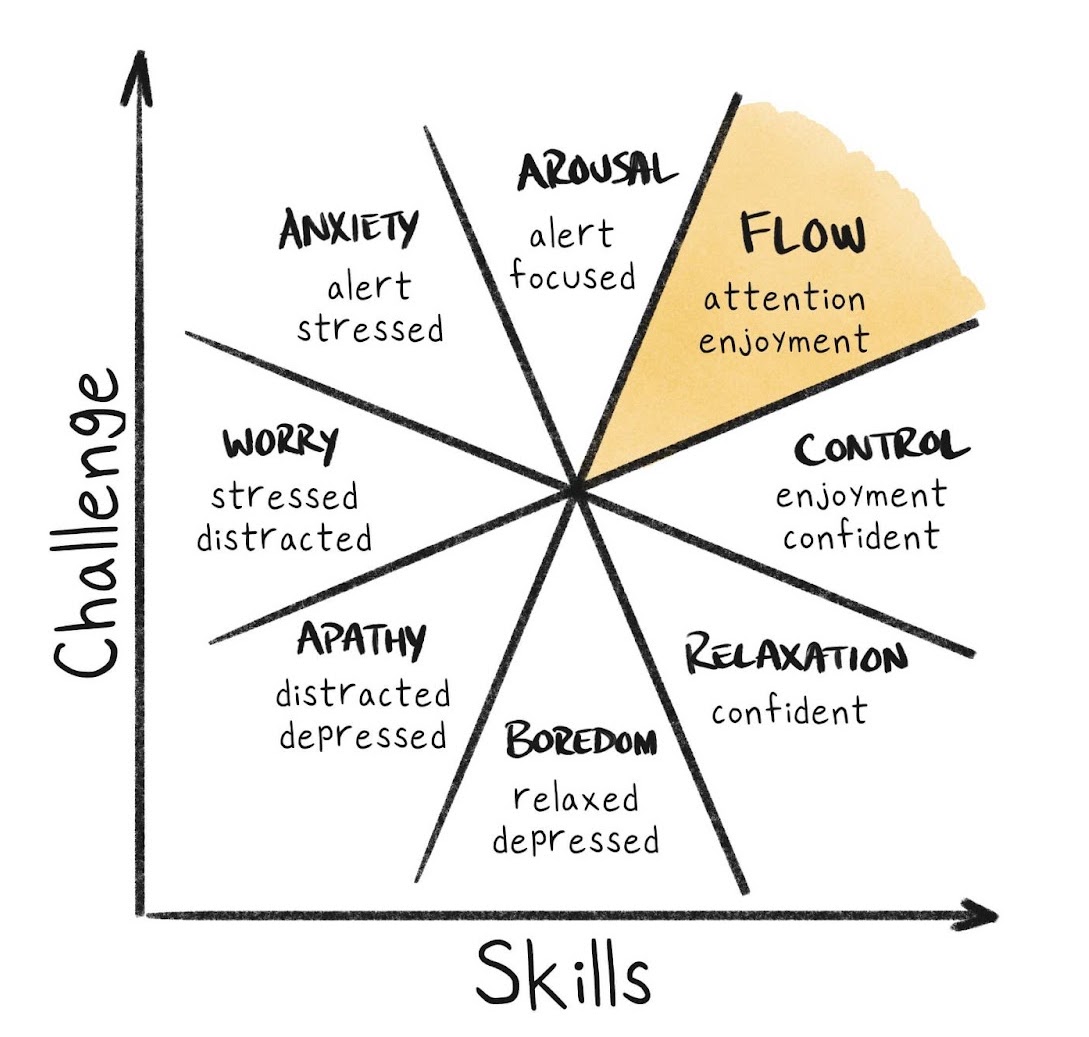

One of the core findings in flow state research is that people need more than just focus to get to a flow state. In the illustration below, for example, you can see how only a particular alignment of skills and challenge leads to flow.

You might be focused on development, but if the particular task is emotionally challenging while requiring little skill, you might just be alert and focused. Similarly, if your current work requires a lot of skill but involves little challenge, you might feel in control and confident but not in flow. The conditions for flow, in other words, might not always be available.

The more I read, the more I realized we all need to upgrade our thinking about flow state. In the decades since Csikszentmihalyi’s initial research, there have been dozens of studies on how developers work.

- A 2023 study found, for example, that there is a huge range of barriers to flow—many of which aren’t just interruptions from coworkers. They categorized these as situational barriers, such as interruptions and distractions; personal barriers, such as the work being too challenging or not challenging enough; and interpersonal barriers, such as poor management and poor team dynamics.

- A 2018 study found, in addition, that the most disruptive interruptions aren’t external—they’re internal. 81% of the participants predicted internal interruptions would be worse, but they were wrong. “Self-interruptions,” the researchers wrote, “make task switching and interruptions more disruptive by negatively impacting the length of the suspension period and the number of nested interruptions.”

These two studies, as well as the dozen or more I read to find these two, give me a theory. There are many barriers to flow, but the worst barriers and the worst interruptions are internal, meaning the development workflow itself needs to improve.

The greatest threat isn’t an external interruption but an internal fragmentation—developers allowing themselves to suspend flow state in favor of important but ultimately distracting tasks.

Good news: We have more power than we think when it comes to maintaining flow. Bad news: We might need to let our coworkers with dumb questions off the hook (at least a little bit).

Why fragmented thinking is the silent killer for developers

I started looking into this not to make developers more productive but to see whether developers who thought they were focusing were really succeeding. I worried that the popularization of “flow state” amongst developers had resulted in many developers thinking they were doing all they could do by turning off Slack notifications or blocking off their calendars.

Fragmented thinking IRL

I don’t mean to be too critical of the common sense assumptions developers tend to make about flow state. That famous comic by Jason Heeris, for example, captures a useful truth.

The comic illustrates that the problem isn’t just restarting work or returning to a task in progress. The interruption shatters a flow state and forces the developer to restart the complex system thinking necessary to solve the problem in front of them.

With this in mind, you can see why a voluntary self-interruption can be worse than an external one. You’re fully shifting your thinking from one task to another—ensuring the flow state and the systems thinking your brain is holding aloft are broken instead of just suspended.

Let’s imagine, for example, that you’re building a feature that depends on an algorithm, and the dependencies involved make the whole problem tricky. For problems like these, higher-level systems thinking is necessary. The problem is too complex and too interdependent.

With that risk in mind, you might insulate yourself from Slack messages and meetings, but standard development practices can break your flow state anyway by fragmenting your focus. As you finish a section of code, you might slip from flow once you go to write a commit message, for example.

But because no one literally interrupted your work, you might be unaware of the costs of that rote, mundane work. You might even castigate yourself over the day for not getting the work done: You fought for a distraction-free day, got it, and you have nothing to show for it. It can feel bad.

Three ways to reduce fragmented thinking

An upside to reframing the problem as fragmented thinking is that there are a lot of opportunities to reduce fragmentation; the downside is that there are a lot of opportunities to choose from. Some take team-wide investment, but you can do individual-level work while you advocate for bigger process changes.

Create mindfulness and nudging practices. A 2018 study focused on good work habits, and a sequel study in 2023 focused on nudging found that reflective goal-setting can increase productivity (80% agreed that daily reflection helped), and regular nudging can help developers better structure their work days and work habits. It sounds simple, but it’s proven to be effective: By being more aware of the productivity and focus threats (especially self-interruption, given what we found earlier), you can make demonstrable improvements.

Reduce tech debt to waste less time. In a 2018 study, researchers found that developers waste 23% of their working time as a result of technical debt. Most of that wasted time comes from performing additional testing, source code analysis, and refactoring. Of course, “Just eliminate your tech debt!” is likely impractical advice, but it points to the fact that a seemingly individual problem, staying focused, is often downstream from an organizational problem.

Make information accessible so you can keep developing. In 2023, as they do every year, StackOverflow surveyed a wide range of developers, and a few of the results are relevant here. According to the research:

-

54% of developers find that “Waiting on answers to questions often causes interruptions and disrupts my workflow.”

-

64% of developers encounter knowledge silos as often as five times per week.

-

63% of developers report that searching for answers and solutions takes at least 30 minutes per day.

Better documentation and collaborative workflows can do a lot to reduce context switching and increase focus. Tooling can also help—consider adopting developer portals and AI-enabled documentation search tools, for example.

Invest in your laziness

Developers, in my experience, already detest useless meetings, and they’re right to protect themselves. If you can also learn the costs of self-interruptions and work toward protecting yourself from fragmented thinking, you can stay in flow even longer.

This work, however, requires some investment beyond the individual. Ask yourself and your organization questions like these:

-

How can teams building internal tools and design systems help to simplify or erase lower-level work?

-

What tooling choices can you make that reduce lower-level thinking and optimize for higher-level thinking?

-

What can you learn from other developers so that you can keep improving your work and development environments?

You can and should be lazy because frenetic, distracted, fragmented work doesn’t lead to productivity or value. Earning the right to be lazy in that way, however, requires team-wide work and organization-wide investment. It’s a challenge, but everyone benefits from meeting it—including the coworker who will no longer have their head bitten off for reminding you of an email about a thing.